On Phrasing

What elements of a performance do we value the most? Certainly we are impressed when a player demonstrates extraordinary facility; we take note and appreciate it when we hear stylistic subtleties. Our attention is held by compelling use of dynamics, and we might smile when we notice distinctive use of articulation. But when we truly feel moved, it is inevitably, at least in part, because of the player's phrasing.

What exactly is phrasing?

First, there is a distinction worth noting. A phrase is a portion of the music that naturally sounds complete, apart from the piece as a whole. It has melodic, harmonic and rhythmic characteristics which communicate wholeness. Quite apart from the phrase, is phrasing. Phrasing is the shaping of small units of music (phrases) into unified, meaningful statements.

This might seem confusing, but think of it this way: phrase, a unit off music, is a noun, while phrasing is a verb. Phrasing is communicating the contents of a phrase in a compelling, readily discernable way. It is the use of the tools of expression--rhythm, dynamics, articulation, tone-- to communicate to an audience a discrete musical idea. It is the telling of a story: phrases have beginnings, middles and ends. It is the effort to bring the audience on a musical journey, one that actually goes somewhere.

When phrasing is clear, it is obvious. When phrasing is ambiguous, that too is obvious. It is the performer's job to convey the music with clarity. This clarity, beyond the clear presentation of the notes, must start with phrasing.

Wikipedia offers this: "The act of shaping a phrase during performance is called musical phrasing and is considered an art."

Get that? "...considered an art." I like that line because it really captures the elusiveness of this element of playing. It is hard to play convincingly without phrasing, yet doing so requires mastery of an art. Not just command of the notes, but mastery of an art.

One of the most curious things about guitar scores is the near total absence of phrase markings. I'd always known this, perhaps subconsciously, but I really realized it when preparing my Chopin edition ("The Complete Chopin Mazurkas," Mel Bay). As a matter of course, I transferred all of the composer's original musical instructions into my arrangements, including tempo fluctuations, dynamics, detailed articulations and phrase markings. When it was fully engraved and formatted, it was obvious it didn't look like any guitar music I'd seen before. It was all those phrase lines! Every page was a beautiful web of graceful curved lines, connecting bits of music of various lengths, usually above the stave but sometimes underneath, connecting material in the bass. This disparity made a strong impression on me. In my original music, published more recently, I made sure every phrase was clearly marked. Once again, the scores do not look like standard guitar music.

Why on earth are there no phrase lines in guitar music?! Our repertoire is most similar to piano music; piano music all has phrase lines. (Note: I'm referring to post-Baroque music). Was it an accident of history? We are accustomed to such tales: notably, the absurdity of the notational standard for guitar being one-stave, in treble clef and transposed an octave, instead of the far more obvious and natural grand staff at concert pitch. It turns out early composers for guitar were violin doublers and, as we transitioned from the use of tablature to mensural notation, they borrowed violin notation for its familiarity. But the lowest note on the guitar is one ledger line beneath the bass clef, the first string open is the lowest line on the treble clef, and the guitar's highest note is one ledger line above the treble clef: a perfect fit. And our repertoire is replete with material in which the separation of treble and bass parts would be well-served by such easy-to-see notation. But no, we are faced with a thicket of ledger lines both up and down, and complex counterpoint all crammed onto one stave. But I understand why this is so. In the case of phrase markings, I have no idea why we have none.

Think of the pedagogical impact of this omission. In the case of piano students, small children are exposed to the concept of phrasing from the very first lessons. Nearly every piece they see has phrase markings. Now, it's probable that there are teachers who don't instill in their students the concepts at issue here, but at the very least, the universal presence of phrases in the music will be assumed by these students and the likelihood that they will play with that in mind will be great.

On the flip side, guitarists never see phrase lines--not when they are young, playing the formative studies, nor as mature experienced players, interpreting the major pieces of the repertoire. If their teachers don't instill in them the need to think and hear in this way, it may not be obvious that they've omitted this critical element in their interpretations.

As an example, I'll show some pages of repertoire for purposes of comparison.

Here is a page of early 19th c. piano music (Mozart, Sonate KV 533):

And here is the same period, but on guitar (Giuliani, Sonata, Op. 15):

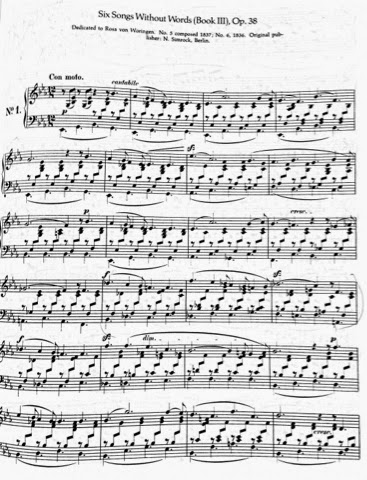

Here is a page of mid-19th c. piano music (Mendelssohn, Song w/o Words, Op. 38, No. 1):

Here is a page of my arrangement of the same piece by Mendelssohn (Song w/o Words, Op. 38, No. 1 [Aron]):

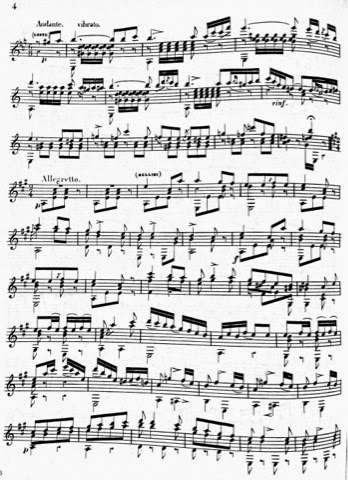

Here is comparable mid-19th c. guitar music (Coste, Fantasie Norma):

Here is another page of mid-19th c. music (Chopin, Mazurka, Op. 59, No. 3):

Here is a page of my arrangement of the same Chopin piece (Mazurka, Op. 50, No. 3 [Aron]):

And here is a piece by a contemporary of Chopin's (Regondi, Etude No. 3):

Here is late 19th c. piano music (Grieg, Moods, Op. 73):

Here is late 19th c. guitar music (Tarrega, Capricho Arabe)

Here is early 20th c. piano music (Joplin, The Augustan Club):

Here is early 20th c. guitar music (Barrios, Mazurka Apasionata):

Here is mid-20th c. Piano music (Boulez, Douze Notations, No. 3):

Here is mid-20th c. Guitar music (Ponce, Sonata III):

Here is late 20th c. piano music (del Tradici, Fantasy Pieces, No. 1):

And a late 20th c. guitar piece (Lauro, Sonata):

(To be fair, many recent and current composers have begun including phrase lines in their scores. See works by Rodrigo, Britten, Walton, Brouwer, etc.)

It would be a laudable project to re-release the entire repertoire in new editions that include phrasing.

But who's to say where the phrases begin and end? Inexperienced musicians often struggle with the task of identifying phrases on their own. And certainly professionals differ in many cases where these delineations should be. It is a matter of style, of experience, of interpretation. But even if strictly editorial, they would have much value.

So, how does one practice phrasing?

In fact it isn't difficult. Identify a musical phrase. After playing the phrase by itself, consider what might make it sound more complete. Maybe a rise and fall in dynamics, or a subtle use of rubato. Maybe a musical breath at its conclusion and before the next phrase begins. Maybe a slight modulation of articulation such that notes at the end become a bit less legato. More likely, though, you'll use a combination of the devices.

The process is fun. Play the phrase in a variety if ways. Try starting loud and then decrescendo; try the opposite. Use your ears and evaluate each effect you get. Exaggerate your ideas, as without a bit of exaggeration, it's unlikely the audience will hear them.

If you simply play every phrase in the following way, you may find your playing sounds more expressive and interesting (if predictable): Start slower than tempo, accelerate gently then slow down again at the end and take a breath before the next phrase. At the same time, start quietly and crescendo to the middle or a bit past the middle then decrescendo and end quietly.

Musical phrases are much like phrases in speech. Depending on what you are saying, you will speak gently or loudly, quickly or slowly, enunciate every sound independently or blur them together, and so on. And practicing phrasing is very much like what actors do. Picture standing in front of a mirror and trying your (spoken actor's) lines over and over, each time with a slightly different character, cadence, or meaning. Now do exactly this on your instrument with the musical phrases before you. Context and style will dictate boundaries and suggest likely solutions, but it's ok to push the boundaries a bit and be creative.

After thinking a lot about rubato while playing 19th c. piano music on guitar, I realized it is ok to suddenly linger on a specific note for special emphasis. I sometimes think of such a note as the word "but," as in speech: the flow might be interrupted by this word, then continue again after a slight pause. Let your music suggest the phrasing. But remember, if you are unclear about the phrasing in your music, so will the audience be unclear about what they are hearing.

Write the phrasing into your scores. Always draw phrasing lines from specific note to specific note, not from region to region. If you were singing, you'd need to know after exactly which note you could take a breath. Think like a singer and be equally specific.

Inexperienced players tend to play either from note to note, or from beat to beat, or, only slightly better, from measure to measure. Once you start playing from phrase to phrase, your performances will sound both more musical and more stylistic; you'll sound more like a classical musician.

(See also my February 2014 post on playing expressively, "Emotional Content in Your Music,")