It is perfectly obvious that there is no place in the world of classical music for performance competition. Competition is well-suited for athletics, in which it is measurable whether a goal was or wasn't made, if one racer touches the finish line before another, etc. It is well-suited to spelling bees or mathematics, in which answers are quite simply right or wrong. But how can this paradigm be applied to the performance of classical music? What we do is so fundamentally subjective that it seems our world would be an inhospitable place for competitive culture to thrive.

The positive aspects of competing are deeper and more varied than your shot at the prize. Consider these:

Getting better from intensive preparation

But no, instead we find competitions in music to be alive and well, to be thriving in fact. This seems at first glance strange, but there are many reasons for it.

First, is the well-established effort to cast our field in the familiar terms of athletics and so possibly attract new and larger audiences. Competitions are events, and events attract attention. Winners and losers are part of the bread and butter of the entertainment industry and so the public is fully trained to think in this way. At the Oscars there are five runners-up for best picture but only one winner. Only one team wins the World Cup, the World Series, etc. Therefore, what could be more natural than a music competition in which several highly skilled players rise to the finals and one is determined to be the best? It makes news for both the sponsors and the winner. This top player, now effectively vetted by the competition, will potentially have an easier time securing engagements or getting better fees, and so on.

Second, producers of guitar festivals have discovered they can guarantee participation in their events if they include competitions. As these smaller, regional events tend to be on small budgets, and smaller competitions are self-supporting (entry fees = prize money), it ends up costing little or nothing to sponsor one. Yet once the competition is added, the event is suddenly populated by a host of serious, experienced players, potentially elevating the level of the music other participants and audiences will hear. Plus, as mentioned, it is perceived as more of an event, so attracts more press than it might have otherwise.

Finally, there is a willing clientele for them. In this arena the old adage is reliable: build it and they will come. After all, young players need opportunities to emerge from the crowd and gain some attention; competitions are an ideal setting to do so.

My contact with competitions has been thick: I have competed and not won (Toronto '84), I have competed and won (GFA '83--4th prize). I have prepared my students to compete; they have won some, lost some. I have produced competitions at my programs, some smaller and regional, others were huge and international with record-breaking awards offered. Finally, I have adjudicated them: local, regional, national and international; adult, high school and youth. And, of course, I've watched them, for years. So I feel I have a reasonable bird's-eye view of this phenomenon from which to make some observations.

Anyone who has tried competing as a classical guitarist knows that the actual moment of performance, especially in the playoff rounds, feels nothing like giving a concert. Venues are normally crummy: fluorescent light-bathed classrooms devoid of good acoustics; no audience to respond to your playing, no applause. Just a small, quiet panel sitting in a row with pens and paper, unnervingly and visibly writing while you play. If they are nice, they thank you when you are finished. Sometimes they just cut you off and send you away. Time limits are typically very short in early rounds, so by the time you realize where you are and what you're doing, your "performance" is over. Every event will be different, though. Sometimes, all rounds take place in acoustically friendly recital halls. Some offer audiences to interact with for second or even first rounds. Some offer travel-expense money to semifinalists who don't make the finals. In every case, though, first rounds will be short, and only in the finals would anyone liken the experience to playing a concert. Even then, traditionally, audience applause is withheld until the performance is over: an artificial construct that takes getting used to.

Playing really well in these circumstances takes practice. It will not be for everyone. Some players will react with unbearable, paralyzing nerves and have difficulty recovering emotionally from a negative result. All this is perfectly normal. But it is far more common that contestants have mixed or mostly positive experiences. And of course, getting promoted to the next round or the finals is a huge boost to the confidence of any participant lucky enough to get good news.

Is competing a good idea? You might wonder if it makes any sense at all. Statistically, your chances of winning are low (higher, naturally, if you are more advanced and experienced). It costs money to do it: travel, lodging, registration fees, incidentals, and necessitates you miss things at home (classes, a job, your freind's recital, etc.). There is a chance you'll choke and play badly or get cut after the first round, having only played for 6 or 7 minutes, and feel lousy about it for days or weeks. So, honestly, is it worth it?

My feeling is that, for most serious young players, and in spite of all these caveats, it is worth it. Consider: most top players, the ones who've won many competitions, still point to the many more competitions they entered but didn't win. It takes practice, repetition, to train yourself to play your best in the odd and artificial setting of a competition. You need to do it repeatedly to get used to it and to excel.

And all the time I'm encouraging my students to enter, part of my calculation is that they will practice REALLY hard and well in preparation, and as a result, they'll get better. To me, this is the guaranteed win they will all walk away with.

And all the time I'm encouraging my students to enter, part of my calculation is that they will practice REALLY hard and well in preparation, and as a result, they'll get better. To me, this is the guaranteed win they will all walk away with.

In most competitions I've been close to, there have been surprises. An earnest underclassman placed while a seasoned doctoral candidate faltered. A dark horse often becomes the winner. Naturally, people gripe and point to supposed "fixes" and seek to find evidence of corruption or favorites, but 99% of the time, it's just plain old adjudication and the law of averages that ends up equalling the result.

The positive aspects of competing are deeper and more varied than your shot at the prize. Consider these:

Getting better from intensive preparation

Performing your music in front of a new audience

Getting heard by professionals, with a chance for feedback from them

Hearing and watching new, unfamiliar players perform

Discovering new repertoire

Testing your own readiness

Discovering the mechanisms and culture of these events, thus demystifying them

Making new friends/contacts

Traveling and seeing new places

In general, I advise my students to enter competitions if they are playing at an appropriate level. If they are less experienced and not ready, but the event is accessible, I recommend they go to watch. It is especially valuable for student guitarists to hear a broader sampling of their serious peers than they hear on a weekly basis. Just listening and watching can transform a student's self-perception and be an unparalleled source of motivation. (Yes, some will claim that watching great playing makes them want to quit, but I don't respond).

Some serious players will eschew competitions altogether, on principal. I respect them! I understand fully and truly sympathize with this position. The artistic goals we cherish, the subtle, personal, subjective nuances of expression which make playing such a rich experience sometimes seem overwhelmed in competitions by more mechanical approaches. Players who are machine-like in the precision of their playing, and who excel at playing fast and loud do sometimes win. And it's hard to deny that oftentimes a certain bland approach to playing is rewarded while inspired and riskier artistic approaches aren't. (On adjudication panels, riskier approaches and outlier interpretations may please one judge but offend another, leading to lower scores, while simple, bland playing can rise to the top out of failing to offend; it is perverse but common).

On balance, though, these skewed results have been less and less common as time has passed. The overall level of playing is so high now, thanks in part to generations of ever-better pedagogy, that winners are almost always undeniably musical, expressive, nuanced musicians in addition to being remarkable instrumentalists with prodigious techniques. In other words, it's not just the fastest players that win.

I still squirm at the notion of subjecting our music to this counterintuitive and vaguely hostile paradigm, and yet, I find myself consistently opting to encourage participation. I accept offers to adjudicate largely in an effort to encourage results that acknowledge originality, true artistry, subtlety, awareness of style differences, and so on, over pure technical prowess. Full disclosure: it doesn't always succeed!

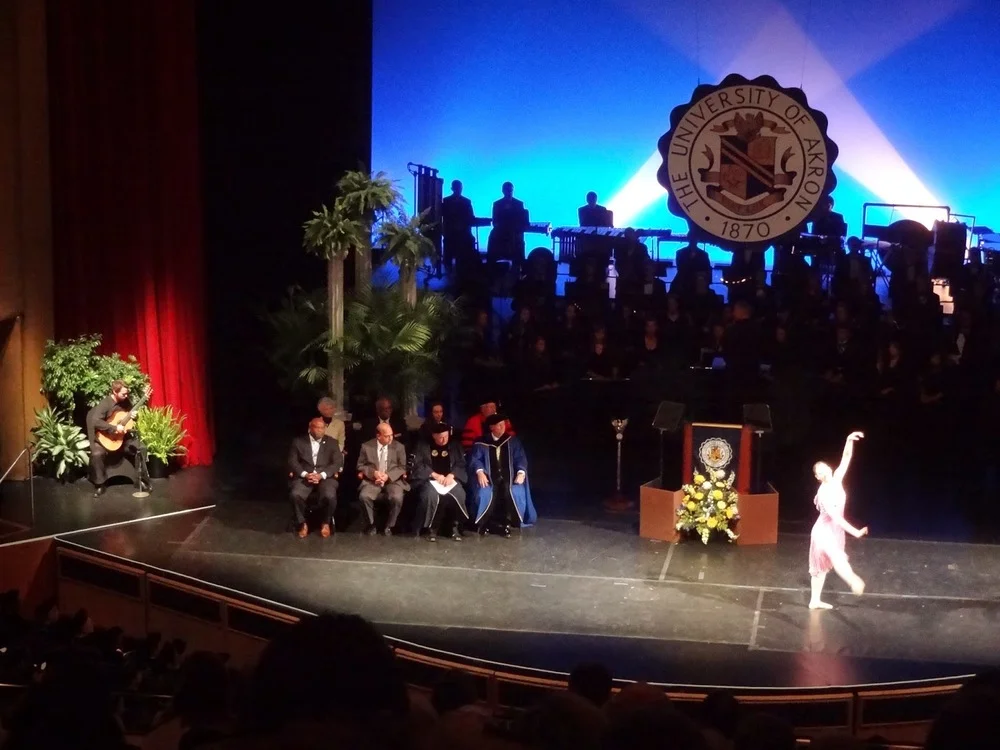

I hosted a terrific competition many years ago in Oberlin, the structure of which I was certain would become the new norm (alas, it wasn't to be). We had live prelims (no recordings) followed by a semifinal that spanned a full five-days. Each evening that week we had a formal concert shared by three of the fifteen semifinalists. Audiences were encouraged to interact normally, that is, to applaud after each piece, not holding back until the end. The community got very excited about this and attended every concert to maximum capacity. We were offering a large prize (the first $10,000 prize in American history for a classical guitar competition), and had attracted the word's finest young players--including eight former GFA prizewinners. The excitement was intense as the week unfolded. Finally, the four finalists, chosen from that field of fifteen, played in the larger hall that Saturday to another, larger, capacity crowd. The semifinalists could all brag that they'd performed on a recital series at Oberlin Conservatory (true), and the winners were plenty pleased to be in the finals. (This was the "GOLD" Competition--"Guitarist of Leadership and Distinction"-1994).

I won't do this again, but it was clear that the participants enjoyed themselves, that everyone was pleased to have been there. Some extraordinary playing was heard, great friendships were formed, careers were launched.

I still squirm at the notion of subjecting our music to this counterintuitive and vaguely hostile paradigm, and yet, I find myself consistently opting to encourage participation. I accept offers to adjudicate largely in an effort to encourage results that acknowledge originality, true artistry, subtlety, awareness of style differences, and so on, over pure technical prowess. Full disclosure: it doesn't always succeed!

I hosted a terrific competition many years ago in Oberlin, the structure of which I was certain would become the new norm (alas, it wasn't to be). We had live prelims (no recordings) followed by a semifinal that spanned a full five-days. Each evening that week we had a formal concert shared by three of the fifteen semifinalists. Audiences were encouraged to interact normally, that is, to applaud after each piece, not holding back until the end. The community got very excited about this and attended every concert to maximum capacity. We were offering a large prize (the first $10,000 prize in American history for a classical guitar competition), and had attracted the word's finest young players--including eight former GFA prizewinners. The excitement was intense as the week unfolded. Finally, the four finalists, chosen from that field of fifteen, played in the larger hall that Saturday to another, larger, capacity crowd. The semifinalists could all brag that they'd performed on a recital series at Oberlin Conservatory (true), and the winners were plenty pleased to be in the finals. (This was the "GOLD" Competition--"Guitarist of Leadership and Distinction"-1994).

I won't do this again, but it was clear that the participants enjoyed themselves, that everyone was pleased to have been there. Some extraordinary playing was heard, great friendships were formed, careers were launched.

I say 'careers were launched.' Well, kind of. Many alliances were formed that expressed themselves later in the form of professional ensembles, or opportunities offered and so on. No one went straight from the GOLD to a contract with Deutsche Grammophon or to major 57th Street management and world tours. The winners just moved forward, a little richer, and with a new bragging point on their dossiers. It's probable that the human connections made were the most valuable and lasting take-away. And human connections were made by everyone, in equal measure--not just the winners.

So, in the end, in spite of the extreme improbability of it, there may be a net positive in these competitive events. It is still important to keep priorities clear, to keep an eye on the big picture. Competing isn't really performing. In performance, the audience's attention is on enjoying the musical journey selected by the player. In competitions, the audience's attention is on comparing the player's prowess to another's while each plays short bits and excerpts, often not of their choice. Performing is a fantastic experience, competing often isn't. I encourage my students to perform a lot. To me, this is what they "major" in. Competing, a parenthetic experience, can help; it can help a lot. But competing isn't what they imagined themselves doing when they decided to play classical guitar--performing is. Competing is merely a tool, an opportunity, a small piece of a large puzzle. As long as this is clear in the minds of the contestants, competing can be a positive experience for all.